Gone, Gone Beyond 360 Real-Space Immersive Cinema

“Hey, hey, have you ever tried… reaching out to the other side?”

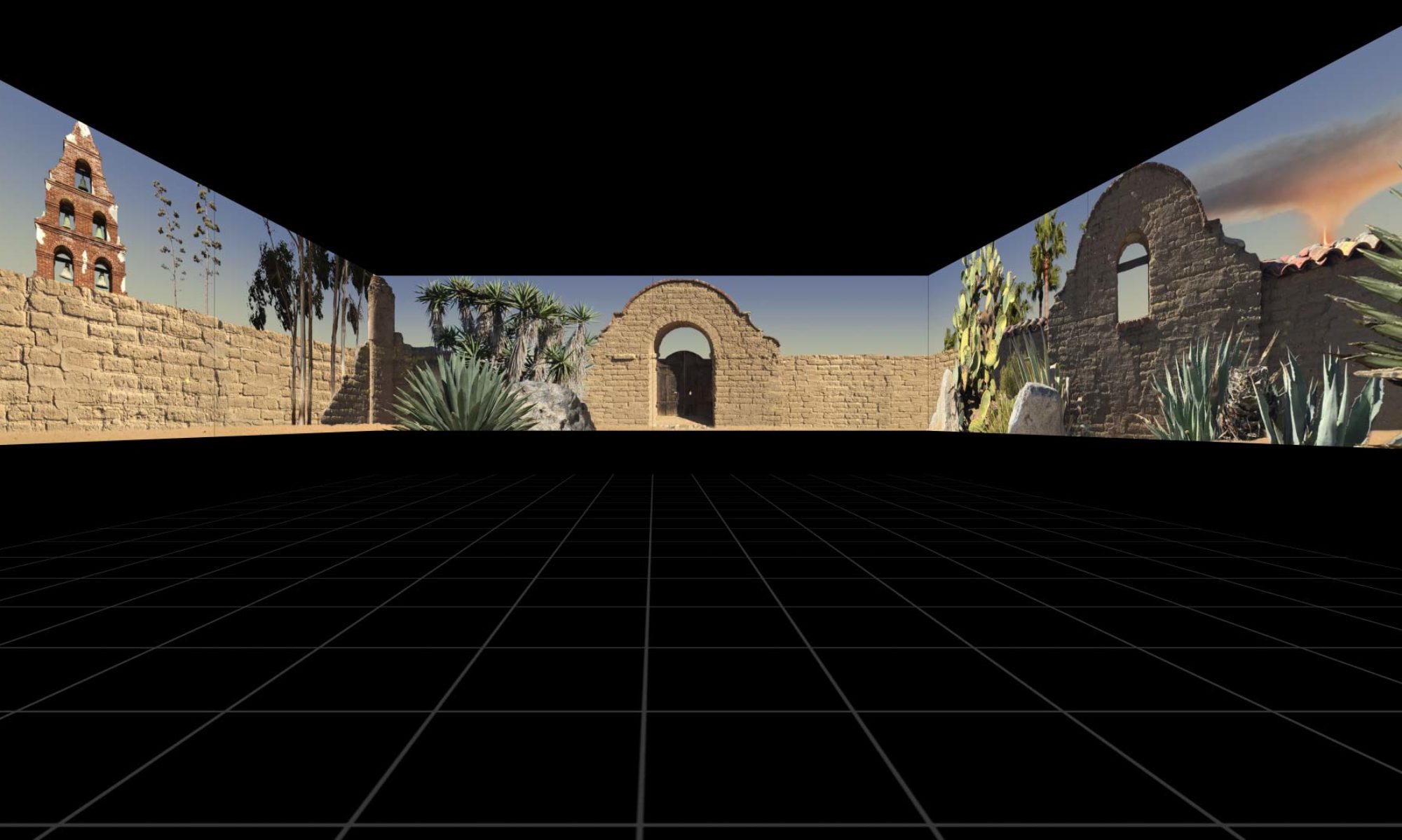

Gone, Gone Beyond is an immersive a/v spatial cinema work by People Like Us (Vicki Bennett), which breaks the rectangle, smashing the thin screen into tiny fragments, looking beyond the frame, climbing through to see what’s behind.

The initial work was commissioned by Naut Humon, the founder of immersive theatre project RML CineChamber, Gone, Gone Beyond is a 10 screen / 6 or 8 speaker piece, with seamless wrap around projection and surround sound where the audience sit inside. It comprises of movie and musical compositions, animated and sample-based/musique concrète collage juxtaposed with content filmed/recorded by the artist, all sewn together in a giant patchwork. Pull on a thread and watch whole new narratives expand and unravel all at once on a 360º palette. The project has been a work in progress since 2017, and showed for the first time in Autumn 2021 in feature length format.

The work’s title and underlying concepts come from the Heart Sutra, a key Buddhist text, describing how all phenomena are empty in form yet ultimately interconnected. The last lines of the Heart Sutra say ‘gate gate pāragate pārasamgate bodhi svāhā’, which means “gone, gone beyond, gone beyond that a bit more, and then beyond that a bit further”. This reflects perfectly the action of going beyond the frame to where there are no edges to the narrative – just emptiness.

In this 360º format, time and space becomes elasticated, with the use of collaged video furthering the reflection on how information comes to us as fragments and that nothing is fixed. A new narrative-thread is woven in the mind of each viewer every time the work is seen, limited only to that exact time and space – just as the Heart Sutra reminds us that the only constant is change, and everything is related with no fixed source.

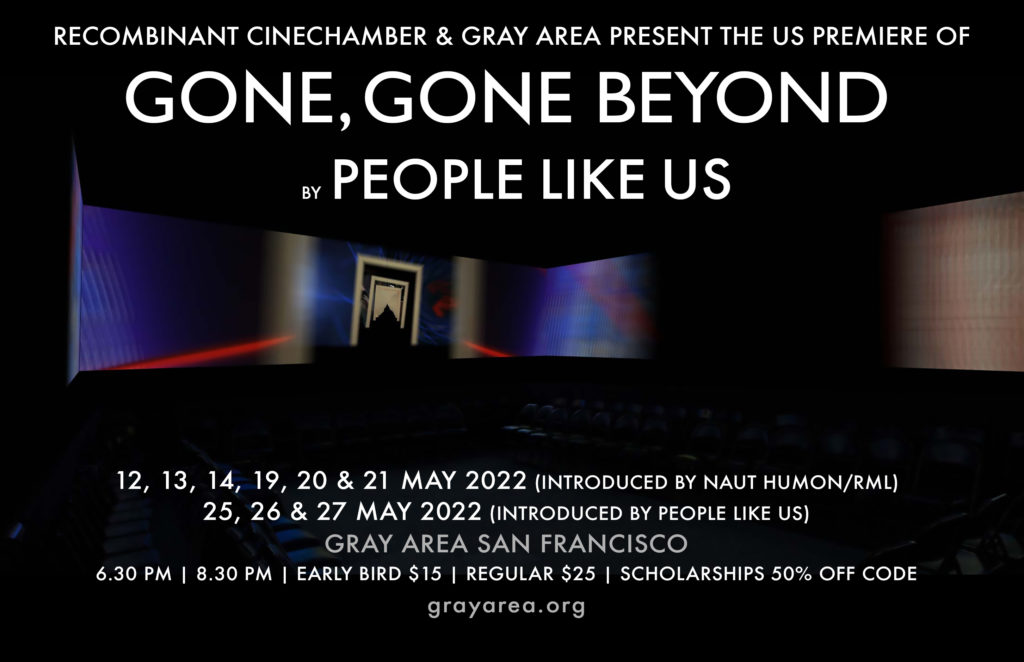

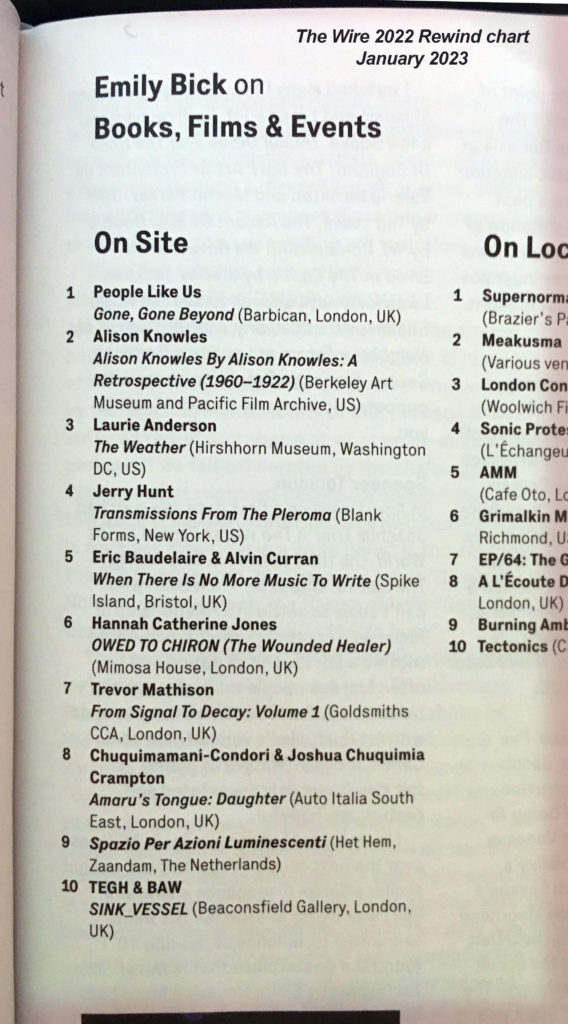

The initial in-process tester movie screened in San Francisco in October 2017 at RML’s own Recombinant Festival at Gray Area Foundation for the Arts. Since then the work has been in development, with a private screening event in April 2019 Goldsmiths SIML for potential partners. The work will screen at nyMusikk, Oslo; SPILL Festival, Ipswich; Attenborough Centre (ACCA), Brighton; and London Barbican, in Autumn 2021. Version 2 of GGB screened in San Francisco’s Gray Area in May 2022 to great critical acclaim.

PAST:

SAN FRANCISCO Gray Area

12-27 May 2022 https://grayarea.org/gonegonebeyond/

OSLO Black Box Teater present KinoKammer with nyMusikk

13-16 October 2021 https://blackbox.no/en/e5115e56-702e-41a2-badb-cb21d1626082/

IPSWICH DanceEast as part of SPILL FESTIVAL

28-30 October 2021 https://www.danceeast.co.uk/performances/gone-gone-beyond-au21/

BRIGHTON Attenborough Centre (ACCA)

4-6 November 2021 https://www.attenboroughcentre.com/events/4028/gone-gone-beyond/

LONDON Barbican Centre

10-13 November 2021 https://www.barbican.org.uk/whats-on/2021/event/people-like-us-gone-gone-beyond

Review in scenekunst.no of Gone, Gone Beyond in OSLO,

http://www.scenekunst.no/sak/psykedelisk-meditasjon/

KRITIKK 15.10.2021 Mariken Lauvstad

KinoKammer

Vicki Bennett (People Like Us) / Lasse Marhaug:

Gone, Gone Beyond + For My Abandoned Left Eye

Black Box Teater / nyMusikk / Double premieres October 13, 2021

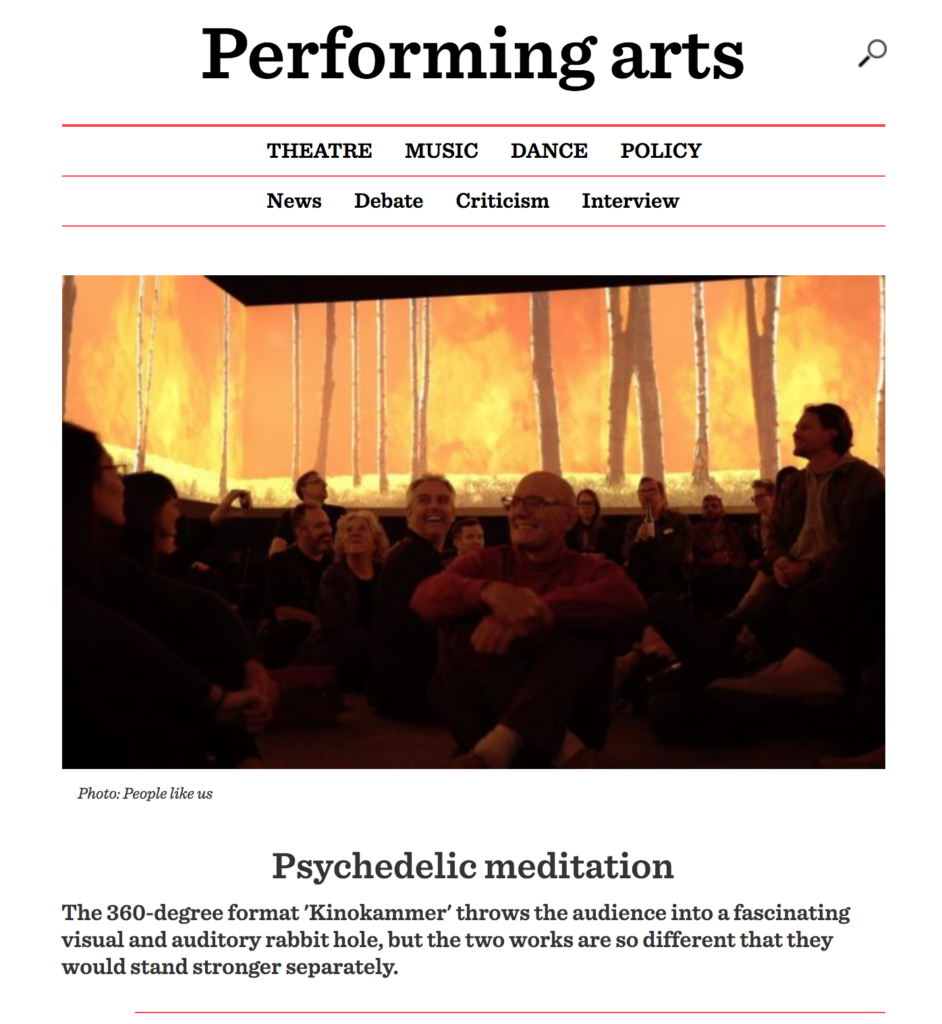

The art event Kinokammer consists of two works made by noise artist Lasse Marhaug and the British video artist Vicki Bennett, better known under the artist name ‘People Like Us’. Both works are world premieres and are shown as a collaboration between Black Box theater and nyMusikk. CineChamber is a cross-genre format based on a concept developed by San Francisco-based Recombinant Media Labs, called CineChamber . The format frames the audience in a 360-degree moving audio and video landscape.

At the Black Box theater, Kinokammer is a so-called double ticket . First Marhaug’s work For My Abandoned Left Eye (2021) and then Bennett’s Gone, Gone Beyond (2021). The public can bring the wine glasses from the foyer into the exhibition hall. Rows of chairs are set up along three of the room’s four walls, while scattered seat cushions are placed on the floor. Thus, the audience will consider other spectators’ eyes and reactions as part of the art experience. Before the screening of Marhaug’s work really begins, an atmosphere is established where small talk and wine drinking are buzzed in the room for several minutes. Whether this is intentional or not, it creates a kind of ‘we’ in the room, an experience of sharing something. This sets a precedent that adds an extra dimension to the art event that will grow and develop throughout the screenings.

Marhaug describes his work as a ‘post-capitalist-science-fiction-noise film’. It is so far a decent genre description, but I experience in a way the work as more ordinary than that, at least visually. We are in a world that is preferably in black and white. We see images and fragments of forest and nature against hard building structures and remains and traces of man-made objects. Garbage, a sneaker, a sofa, an animal foot. The totality appears raw, wet, cool and hard, not only visually, but also acoustically. Occasionally, the film material is contrasted by abstract images, such as massively pulsating black spots, close together against a white background.

A mass bombardment that challenges the senses

Each projected movie sequence apparently has its own and ever-changing soundtrack. This constantly creates new and different layer-on-layer effects. The soundscape gives, among other things, associations to machine repetitions and massive metal grinders against crackling and crackling in various qualities, auditory textures that for a few moments remind me of the feeling of stinging icy rain or penetrating intense wheezing in the ears. Suddenly, small interruptions occur with the absence of noise before new images and sounds are fired at us like projectiles. It is a mass bombardment that challenges the senses and the distinction between impression and disturbance. Finally, I’m not sure if I actually hear sampled cries, the noise of a full room of screaming people, or if it’s just my brain that tricks me into thinking I sense these cries through the noise. I go out filled with a kind of unpleasant dizziness and with aching retinas. The work leaves an eco-deterministic turmoil in me that I need far more than thirty minutes to digest and reset myself from, and this also constitutes my objection to two such different works being put together.

After the break, we are thrown out on a completely different journey. This time, some have lain down on their backs, some close their eyes, some just sit relaxed and sip on the evening’s second or third glass of wine. All four walls are projected close together with flaming candles. The picture is obviously strikingly kitsch, almost ironic. Gradually we can hear sounds reminiscent of a crowd of stomping boot steps mixed with an indefinable hiss from insects and crickets, and a diffuse hum from distant, manipulated choruses. It is difficult to interpret and place the soundscape, and I also do not have time to get very far before the whole room is almost sucked through a kind of visual tunnel. The bass makes the floor below us vibrate, and we are pulled at breakneck speed through countless projected doors. This estimate reinforces the illusion of being in a simulator. It is as if a virtual wind has suddenly blown us away and we are suddenly sitting on a flying carpet, traveling through the artist’s subconscious, where playful pop cultural references are replaced by nightmarish and disturbing images. The audience looks in all possible directions as if to orientate themselves in constantly new places.

As if David Lynch were to take ayahuasca in the desert

The editing technique is extremely good, and the dramaturgy has a kind of kaleidoscopic associative form at the same time as each picture is just so easy to interpret that you can get caught in a new hook that throws you in the head. new associations before being torn loose and thrown into the next. This is as if David Lynch had taken ayahuasca in the desert and made a film of what he hallucinated afterwards. We are constantly somewhere between dream and nightmare, for example when we see Julie Andrews dancing carefree between tree trunks while war helicopters thunder across the sky while the world goes up in flames and explodes around her. We see prairie pictures with saguaro cacti and hear the sound of unpleasant radio signals. The chimney sweep from Singing in the Rain disappears into animated pipes, we see oil barrels burning and growing nebulae, barely hearing the sound of Joni Mitchell’s ‘Both sides now’, glimpsing the globe from space (or is it a disco ball?), being drawn to the sound of lyre boxes and suddenly surrounded by giant funfair horses.

In the popular cultural references, a darker contemporary commentary is hidden. Most of the references are from the 1950s, 60s and 70s, and in contrast to beautiful images of the universe’s darkness, celestial bodies and galaxy fog, an experience is created that time flows through space and pulls us through the cosmos at relentless speed. The work opens the gaze to the paradoxical and random of our popular cultural history, the powerless and merciless in that we have created what we have created, and nothing else.

The work also makes me philosophize about what can be called a performance. There are no actors or actors here, but I experience in return that we audiences become part of it. At one point a man rushes out of the room, a woman overturns a bottle, some get up from their chairs and walk around smiling or looking. None of this bothers me as it would in many other contexts. At one point there is one who laughs, and after this it is as if something in the room dissolves, the reactions become freer and more expressive. People respond and come up with small exclamations. The work would therefore not have been the same if I experienced it alone, and then maybe it’s a performance anyway?

In sum, I still think the two parts of tonight’s double ticket should have been shown separately. They are both so strong and intense works that they leave different resonances and reflections it would have been nice to have time to dwell on separately.